Growing laboratory-engineered miniature human livers

I enjoyed eating cow liver as a kid. I never understood why so many kids thought it was bad. It was and still is one of my favorite foods. Now, one day soon, I might just be able to grow my own livers for snacking anytime I'd like. And the bonus is that if my own liver wears out or fails I might be able to have a surgeon pop a new one in.

The ultimate aim of the research carried out at the Institute for Regenerative Medicine at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center is to provide a solution to the shortage of donor livers available for patients who need transplants. Additionally, the laboratory-engineered livers could also be used to test the safety of new drugs.

The livers engineered by the researchers are about an inch in diameter and weigh about 0.2 ounces (5.7 g). Even though the average weight of an adult human liver is around 4.4 pounds (2 kg), to meet to minimum needs of the human body the scientists say an engineered liver would need to weigh about one pound (454 g) because research has shown that human livers functioning at 30 percent of capacity are able to sustain the human body.

“We are excited about the possibilities this research represents, but must stress that we’re at an early stage and many technical hurdles must be overcome before it could benefit patients,” said Shay Soker, Ph.D., professor of regenerative medicine and project director. “Not only must we learn how to grow billions of liver cells at one time in order to engineer livers large enough for patients, but we must determine whether these organs are safe to use in patients.”

How the livers were engineered

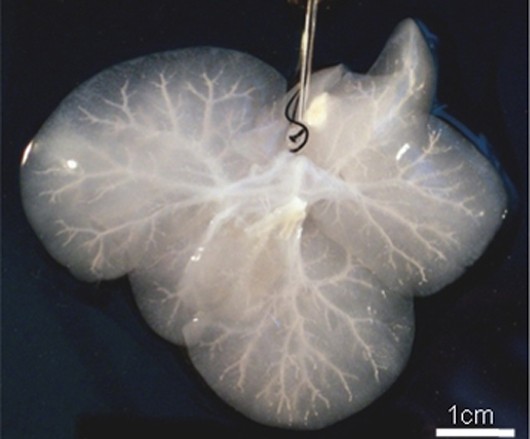

To engineer the organs, the scientists took animal livers and treated them with a mild detergent to remove all cells in a process called decellularization. This left only the collagen “skeleton” or support structure which allowed the scientists to replace the original cells with two types of human cells: immature liver cells known as progenitors, and endothelial cells that line blood vessels.

Because the network of vessels remains intact after the decellularization process the researchers were able to introduce the cells into the liver skeleton through a large vessel that feeds a system of smaller vessels in the liver. The liver was then placed in a bioreactor, special equipment that provides a constant flow of nutrients and oxygen throughout the organ.